Abstract

Purpose

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) reduce acid secretion in the stomach and rank as one of the most widely used acid-suppressing medicines globally. While PPIs are safe in the short-term, emerging evidence shows risks associated with long-term use. Current evidence on global PPI use is scarce. This systematic review aims to evaluate global PPI use in the general population.

Methods

Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts were systematically searched from inception to 31 March 2023 to identify observational studies on oral PPI use among individuals aged ≥ 18 years. PPI use was classified by demographics and medication factors (dose, duration, and PPI types). The absolute numbers of PPI users for each subcategory were summed and expressed as a percentage.

Results

The search identified data from 28 million PPI users in 23 countries from 65 articles. This review indicated that nearly one-quarter of adults use a PPI. Of those using PPIs, 63% were less than 65 years. 56% of PPI users were female, and “White” ethnicities accounted for 75% of users. Nearly two-thirds of users were on high doses (≥ defined daily dose (DDD)), 25% of users continued PPIs for > 1 year, and 28% of these continued for > 3 years.

Conclusion

Given the widespread use PPIs and increasing concern regarding long-term use, this review provides a catalyst to support more rational use, particularly with unnecessary prolonged continuation. Clinicians should review PPI prescriptions regularly and deprescribe when there is no appropriate ongoing indication or evidence of benefit to reduce health harm and treatment cost.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are weakly basic acid-labile pro-medicines that reduce acid secretion in the stomach [1]. PPIs are a class of medicines which include omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, and dexlansoprazole.

PPIs are the cornerstone in the management of gastric and duodenal ulcers, dyspepsia, gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), Zollinger–Ellison (ZE) syndrome, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication, and prevention and treatment of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID)-associated ulcers [2, 3]. There is also widespread “off label” use for prophylaxis against gastritis associated with corticosteroids, anticoagulants, chemotherapy, and coronary heart disease [4, 5].

Given the utility of these medications, safety profile, efficacy, and tolerability, their usage globally is significant. In 2020, omeprazole was ranked as the second-highest dispensed item in England, with almost 35 million prescriptions filled and an annual cost of GBP 82 million [6]. In the USA, omeprazole was the eighth most commonly prescribed medication in 2019 with more than 52 million prescriptions [7]. The USA spent $19.99 billion in 2016–2017 on PPIs [8].

Although PPIs are generally considered safe for short-term use, evidence of serious side effects with long-term use is mounting. These potential risks include increased risk of pneumonia, enteric infection, bone fracture, gastrointestinal tract cancers, and reduced absorption of vitamins and minerals [2, 9].

Indications that require long-term PPI use are limited. Apart from some specific acid-related diseases (e.g., ZE syndrome and Barrett’s esophagus (BO)), it is recommended that PPIs should be discontinued 4 to 8 weeks after initiation [2, 9].

Despite the wide prevalence of their use, cost to health care systems, routine “off-label” use, and evidence that these medications are used for longer than recommended; no systematic reviews have been conducted to examine global trends and practices of PPI use.

We have undertaken this review to fill this appreciable gap in the literature and comment on PPI use in the general population, medication factors (dose, frequency, duration, and PPI type), and demographic factors (age, sex, and ethnicity).

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in line with Cochrane recommendations [10] and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [11]. The protocol for this review was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42020167968) [12].

Study inclusion criteria

Observational studies (cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort studies) that reported population level PPI use were considered eligible.

Studies were excluded if they were not deemed to be representative of the general population. For example, studies of only males OR females or studies who recruited specific subsets of the population (with pre-existing condition or other medication use).

Hospital use of PPIs was excluded as these may be used for stress ulcer prophylaxis or as a short-term symptomatic relief. However, if the hospital setting was used to recruit long-term PPI users or recruited patients with PPI use on admission, these studies were included. Clinical trials, conference abstracts, case-reports or case series, commentaries, editorials, letters, and non-English articles were not eligible.

Search strategy

Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA) were systematically searched from inception to 31 March 2023 to identify observational studies on oral PPI use (liquids and capsules) among individuals aged 18 years and older in the general population. The detailed search strategy is provided in Supplementary File 1.

After removing the duplicates, the references were imported into Excel. Two reviewers (L.G.T.S. and R.B.) independently screened titles and abstracts, and then full text, to assess for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the two reviewers or arbitrated by a third reviewer (S.P.). Reference lists of eligible studies for the full-text analysis, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses, were further hand searched manually by two reviewers to identify any additional articles. Where multiple studies reported from the same data source, the study with the longest time period with the largest number of participants and the highest number of utilization variables was included.

Data extraction

The following information was extracted from all eligible studies following a template from a previous systematic review [13]: (A) article information (first author and year of publication), (B) study characteristics (country, study period, study design, study setting, and source population) and PPI population (i.e., the population from which eligible PPI users were drawn), (C) patient’s characteristics, and (D) medication characteristics and possible indication. If the data were presented in graph form only, the values were extracted using WebPlotDigitizer version 4.2 [14]. For studies presenting sequential years of national sampling, the most recent year was used to retrieve the data.

PPI use was classified by both [1] patient’s demographics (age, sex, and ethnicity) and [2] medication factors (dose and/or frequency, duration of PPI use, and PPI type) when possible.

Participants of each study were categorized as “prevalent PPI users” (i.e., patients who had already been prescribed PPIs before study recruitment and continued the medicine throughout the study period) or “new PPI users” (i.e., PPI naïve; PPI therapy was newly started and had long-term follow-up data) based on the information provided. Each utilization variable is reported stratified by user type (i.e., new users only and total users (prevalent + new users)).

Extracted variable standardization

The categories for each variable were not pre-defined, and they were developed by the review team to best capture the majority of available data from individual studies.

Age

Participant age was categorized into three groups (≤ 49, 50–64, and ≥ 65 years old) based on the available data.

Sex

All studies reported on sex or gender by binary classification only (male or female).

Ethnicity

Studies described ethnicity or race differently, using terms such as: White, Black, Asian, Caucasian, African American, Hispanic, Asian, and Other. We collapsed these terms into four groups (White, Black/African American, Asian, and Other).

PPI types

Data were provided on overall PPI and by specific PPI such as “Omeprazole,” “Esomeprazole,” “Pantoprazole,” “Lansoprazole,” and “Rabeprazole.” For less common PPIs such as dexlansoprazole or other PPI combinations, we categorized these as “Other.”

Dose

Studies described doses differently, using terms such as: higher dose, maintenance dose, lower dose, and on-demand, that is taking PPI intermittently, when experiencing symptoms. We considered this dose categorization.

For the purposes of this review, higher dose was defined as equal to or higher than the defined daily dose (DDD), while lower dose was defined as being less than the DDD. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the DDD as the “assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults” [15].

Dose frequency information was clustered into once daily, twice daily, on-demand, and other.

Duration

We defined duration of PPI use as either “Short-term” (defined as less than one year) or “Long-term” (defined as greater than one year).

To identify whether PPI use practice complied with current treatment guidelines [2, 9], we calculated the number of users who were on prescriptions of three months or less. Long-term users were further stratified into one year to three years and more than three years use.

Indication

Indication for use was clustered into eight categories based on clinical similarities. These were gastroprotection (GI irritant medicine or treatment side effects), dyspepsia/GERD, gastritis/duodenitis, ulcer/GI bleeding, H. pylori infection, BO/ZE syndrome, uncertain/unknown indication, and other.

On request during peer review, a sub-analysis was undertaken for studies reporting on utilization prevalence, incidence, and characteristics of users that were fully generalizable to the country’s population.

Statistical analysis

The utilization variables were descriptively assessed using percentages. All analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (2019).

The absolute numbers of PPI users for each subcategory within a variable were summed up, and the percentages were computed using the total number of individuals for that variable as the denominator.

E.g.,

Total PPI users for age variable = a.

Number of PPI users younger than 40 years = b.

Percentage of PPI users younger than 40 years = (b/a) × 100.

Results

Description of included studies

The process for identifying the included studies is shown in Fig. 1. Online searches identified 4598 records, of which 638 were duplicates. The remaining 3960 articles were screened by titles and abstracts, with 925 articles then screened as full text. The 65 articles identified as eligible to our research question are described in Supplementary Table 1.

Eligible studies were carried out between 1988 and 2022 and included data on 28 million prevalent and new PPI users (ranging from 32 to 4,388,586 PPI users in each study). The sixty-five [8, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79] included studies were from 23 countries, with all the data from developed countries except Colombia [51], Iran [31], and Mexico [66] (Fig. 2).

PPI utilization in the general population

Out of 65 studies, 28 reported the source population. From these studies, it was estimated that 23.4% of the adult source population in the world were PPI users (18,326,284/78,151,104). Table 1 presents the number of studies eligible for the analysis of each utilization variable.

PPI utilization by age

Figure 3 depicts population utilization data across age groupings. Out of 65 studies, 26 total user (prevalent + new PPI users) studies (N = 6,382,619) were eligible for age analysis. Lassalle et al. were excluded from the age analysis as it highly skewed the results due to the broad binary age categorization (18–65 and > 65 years) utilized in the study [48].

Percentage of PPI users included in this review, stratified by age groups. Total users’ (prevalent users + new users) data from 26 studies (N = 6,382,619); new users’ data from 15 studies (N = 5,060,973). *Excluded, i.e., age categories reported in eligible studies were outside the age bands used for this analysis (e.g., < 55, > 45, and 18–65) (all users = 4.2% and incident users = 3.2%)

Out of 6,382,619 total users, 5,060,973 (79.3%) new users (N = 15 studies) were included for age analysis (Fig. 3).

PPI prescriptions were most common in the oldest and young to middle age bands in the total user analysis (Fig. 3). People 65 years and older comprised 37.1% (2,367,849/6,382,619) of total users, and 34.7% of total users were ≤ 49 years (2,213,802/6,382,619). However, the percentage of young to middle aged adults (38.8%; 1,964,469/5,060,973) is higher than the older people (33.2%; 1,678,751/5,060,973) in the new user analysis (Fig. 3).

Four percent (total users; 4.2% (269,856/6,382,619) and 3.2% (new users: 162,872/5,060,973) of age data were excluded from analysis as those age data were outside the age bands used for this analysis (e.g., < 55, > 45, and 18–65) (Fig. 3).

PPI utilization by sex

Sixty studies had sex information for both prevalent and new PPI users (N = 23,153,964). Among total users, 91.4% (N = 21,158,936) were new users (N = 25 studies). Over half of the population were female (total users = 56.1%; 12,990,358/23,153,964; new users = 56.1%; 11,878,481/21,158,916).

PPI utilization by ethnicity

Nine studies provided ethnicity information for total PPI users. Seventy-five percent of the total population was White followed by Black/African American (15.6%) and Asian (1.3%). Only two studies had data for new users, and the distribution was the same as total users including that nearly 80% were White.

PPI utilization by medication types

Thirty-one studies and 12 studies reported data for PPI types for total users and new users, respectively. Omeprazole was the leading PPI used, accounting for 44% of both total users and new users. Over one-quarter of total users (26.1%) and new users (26.6%) were prescribed esomeprazole; making it was the second-most prescribed medicine (Table 2).

PPI utilization by dose

PPI dose information was available in 15 studies. Out of 15, seven (19, 24, 37, 41, 46, 56, and 79) categorized dose according to the strength of the prescribed dose, that is higher dose, maintenance dose, lower dose, and on-demand (Table 2). Moriarty et al. [56] and Cahir et al. [19] had identified pantoprazole 40 mg/daily as a higher dose while Hughes et al. [41] and Yap et al. [79] defined it as a standard dose. Because of the inconsistent reporting of doses especially higher dose, the results are shown under two analyses (i.e., higher vs. lower dose and higher vs. maintenance dose) (Table 2). Only one study provided data on new users [24]; hence, a separate new user analysis was not performed for dose variable.

Almost all users utilized the higher dose, with only approximately 2% utilizing the lower PPI dose (Table 2: dose (A)). A sub-analysis was performed using three studies (19, 24, and 56) (N = 225,280 of total users) that had the same definitions for higher and maintenance dosing (Table 2: dose (B)). Nearly two thirds of total users were on a higher dose (143,466/225,280; 63.7%), whereas 36.3% (81,805/225,280) were prescribed the maintenance dose. None of the studies had lower dose PPI users (Table 2: dose (B)).

Eight studies had reported dose according to the frequency of regimen (23, 25, 30, 31, 38, 42, 58, and 71). Sheikh et al. was removed from the frequency analysis as this study combined once and twice daily data [71]. Table 2: dose (C) shows that nearly eight in 10 users were prescribed a once a day regimen, followed by on-demand PPI prescriptions (11.1%).

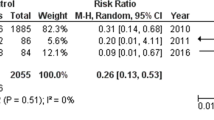

PPI utilization by duration

Over 5 million total users were available for duration analysis in 22 studies. More than two-thirds were short-term users (< 1 year) (Fig. 4). Of them, nearly 45% (1,583,705/3,549,848) discontinued their PPI use within the first three months.

Numbers of people who used PPIs included in this review, stratified by duration groups. Total users’ (prevalent users + new users) data from 22 studies (N = 5,266,213); percentage of short-term users (< 1 year) vs. long-term users (≥ 1 year) (67.4% vs. 25.1%). New users’ data from 5 studies (2,450,952); percentage of short-term users (< 1 year) vs. long-term users (≥ 1 year) (80.9% vs. 18.9%; P < 0.001). *Excluded, i.e., duration categories reported in eligible studies were outside the duration bands used for this analysis (e.g., > 8 weeks, > 3 months, and 6–24 months) (all users = 1.3% and incident users = 0.2%)

One-quarter of total users (1,314,544/5,266,213) were long-term users with one year or longer PPI prescriptions (Fig. 4). Among them, nearly two-thirds continued their prescription for one year to three years (65.5%; 861,357/1,314,544), while 27.8% (365,659/1,314,544) continued for more than three years.

PPI utilization by indication

The indication for PPI prescription was described in 32 total users’ studies (Table 2). Prophylactic prescribing of PPIs for NSAIDs, antiplatelet therapy, aspirin, corticosteroid, and chemotherapy was the most prevalent indication, while dyspepsia and GERD were the second most common indication for both total and new users (Table 2). The results showed that over 2.8 million PPI users (14.6% of total users and 15.4% of new users) had uncertain or no indication for PPI prescription recorded.

Out of 65 articles, eleven studies reported the PPI utilization rates (i.e., prevalence and incidence) along with the characteristics of users that were fully generalizable to the author’s country population. The summarized results of those studies are reported in the next section.

Prevalence of PPI utilization

Studies where prevalence rates were reported showed large variability in the percentages of population estimated to be using a PPI at a particular time point (4.4–33%) [8, 26, 33, 37, 48, 57, 60, 62, 64, 65, 72]. These were further analyzed as trends over time, with most showing a pattern of increasing use with time [8, 26, 33, 37, 48, 57, 60, 62, 64, 65, 72] (Table 3). Comparing the studies with similar observation periods showed a relatively constant annual incidence rate, while the prevalence rate continued to rise (annual incidence rate: France (Pays de la Loire region): 1.2–2.0 per 100 persons (2017–2020) [33]; Iceland: 3.3–4.1 per 100 persons (2003 to 2015) [37]; Denmark: 2.1–3.6 per 100 persons (2002–2014) [62]; Israel: 2.4–3.1 per 100 persons (2000–2015) [64]). Over the study period, the prevalence rates were two to five-fold increase in Iceland, Denmark, and Israel (Iceland: 8.5–15.5 per 100 persons [37]; Denmark: 1.8–7.4 per 100 persons [62]; Israel: 2.4–12.7 per 100 persons [64]). Similarly, PPI use increased in Spain by 44.8% from 2002 to 2015 (12.5% in 2002 to 18.1% in 2015) [72] and the USA by 18.1% from 2002/2003 to 2016/2017 (from 5.7% in 2002/2003 to 6.7% in 2016/2017) [8]. The PPI use in the UK [60] and Australia [26] were 7.7% (2014) and 12.5% (2016), respectively (Table 3).

Prescribing patterns

As seen in the full systematic review data, initiation of PPIs occurred more frequently in those of young to middle age (46 years to 57 years) [26, 37, 48, 57, 60, 62, 64, 65, 72]; however, there was an increased trend in PPI use with age particularly among adults aged 65 years and older (USA: 37.8% (≥ 65 years) vs. 2.08% (18– < 25 years) [8]; Iceland: ~ 40.0% (≥ 80 years) vs. ~ 8.0% (18–39 years) [37]; Denmark: > 20.0% (≥ 80 years) vs. ~ 1.0% (18–39 years) [62]; UK: 23.0% (≥ 80 years) vs. 1.0% [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30] [60]; Australia: 42.8% (≥ 85 years) vs. 4.5% (18–34 years) [26]; Germany: ~ 40.0% (≥ 90 years) vs. < 5% (20– < 25 years) [65]; Spain: 61.0% (≥ 65 years) vs. 2.0% (16–24 years)) [72]. The prevalence of PPI use is more common among females [26, 37, 48, 57, 60, 62, 64, 65] (Table 3).

While omeprazole remained the most used PPI in almost all countries, Denmark [62], Switzerland [57], and Germany (Bavaria region) [65] had a greater utilization of pantoprazole. Over the time periods, some shift from omeprazole (racemate) to esomeprazole (isomer) was seen (Table 3).

Doses/duration

Most PPI users maintained their initial strength throughout the course of treatment without any dose adjustments [26, 37]. It was found that a larger proportion of higher dose users remained on this dose for a longer period. In Iceland, 13.0% of higher dose users continued the same dose for five years, in contrast to 2.0% of lower dose users [37].

Most of the studied countries had a considerably large proportion of long-term users (16.0%, 22.0%, and 26.7% of users continued for at least one year in Australia, Iceland, and the UK, respectively) [26, 37, 60] (Table 3).

Long-term use of PPIs increased with age (e.g., in Iceland, 36.0% of people older than 80 years continued the treatment for one year after initiating the PPI prescription, compared to 13.0% aged 19–39 years) [37]. The same kind of age pattern was observed in Denmark [62], Israel [64], France [48], and Spain [72].

Discussion

This systematic review is the first to describe global PPI use patterns by demographics and medication factors and is based on published literature over three decades. The findings of this review provide robust evidence on actual PPI use in the general population, which in turn provides information to develop and update PPI prescribing policies to improve the safety of PPI use.

In this review, 65 papers were analyzed and generated a total PPI user group of 28 million across 23 countries, representing 23.4% of the adult population. The results showed that the prevalence of PPI prescribing has steadily increased from 1990; however, the rates have declined recently in some countries, e.g., Germany [65], the USA [8], and Spain [72]. The incidence rate of PPI prescribing remained relatively stable over time, implying that the observed higher prevalence rate is due to a growing number of long-term users. The observed rate stabilization could be attributed to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s [80, 81] safety warnings and recent findings from observational studies highlighting the potentially deleterious consequences of long-term usage [80, 81].

PPI use was largest among adults aged 65 years and older, followed by the young to middle aged group (≥ 65 years old: 37.1% of total users and ≤ 49 years old: 34.7% of total users, respectively) (Fig. 3), females (56.1% of total users), and White ethnicity (75.0% of total users).

Despite clinical guidelines recommending the lowest possible dose for the shortest duration (generally 4–8 weeks) [2, 8], this systematic review has observed PPIs being prescribed in higher doses (63.7% of total users) and for longer periods (≥ 1 year: 25.1% of total users). Of long-term users, 65.5% continued for up to 3 years, and 27.8% continued for over three years. These findings were consistent with the national level data and showed that 16.0–26.7% of PPI users had continued therapy for longer than one year [26, 37, 60],

The data of this review is insufficient to find the specific reason for the use of PPIs at an individual patient level. Increased prevalence of GERD in younger patients [82] and inappropriate prescribing for stress ulcer prophylaxis [48, 83] or co-prescribing with NSAIDs [48] or no indication [65] may increase PPI use, particularly in young and middle-aged groups.

The global prevalence of PPI use is increased among older adults and may be as a result of multiple comorbidities, increased risk of acid-related gastrointestinal disorders, polypharmacy, and lack of deprescribing [84, 85]. Recent studies show both the need and emphasis on reducing inappropriate use of PPIs in those over 65. Hence, deprescribing of inappropriate PPIs in older adults is a growing area of interest [86, 87].

It is important to note that much of the data for this analysis came from “Western” countries (North America, Europe, and Oceania) and data from Africa, Latin America, Russia, and some parts of Asia (China, India, and Pakistan) were not available. Market research reports indicate the Asia Pacific region holds the fastest growing PPI market [88, 89], while Latin America and the Middle East regions are more likely to have a large PPI market due to increased GERD prevalence [90]. Hence, a greater understanding of PPI use in these countries is warranted.

Esomeprazole—(S)-isomer of omeprazole—has an identical mechanism of action and is a therapeutically interchangeable high-cost medicine. However, this was the second most common PPI found in this review. When there is no clinical benefit to an alternate medicine, prescribers should consider cost and patients’ affordability when prescribing medicine.

Limited data on PPI user’s ethnicity variable limits the opportunity to calculate PPI use rates per ethnicity. Ethnicity was recorded for 215,119 users (out of 78,151,104 of the source population), representing only 0.3% of the source population. Hence, more studies are warranted to investigate the PPI use by ethnicity.

Another scope of the analysis was to evaluate the dose and duration of PPI use by indication, which would explicitly provide information on whether the prescribing has adhered to the current treatment guidelines [2, 3, 9]. However, this sub-analysis was not feasible as none of the studies provided data for this hypothesis. Hence, further work is required to understand the reasons for PPI use at a higher dose and longer than the guidelines recommend.

The current review provided evidence for only prescribed PPIs but not for OTC (i.e., available via a pharmacy/supermarket without prescription) use. The prescription use of PPIs dates back to 1988; however, OTC availability was initiated in the early twenty-first century and is seen in many countries, including the USA, the UK, Sweden, and New Zealand [91,92,93]. Generally, OTC medicines are more expensive, and a supply period is less than a month. As this review assessed the long-term use of PPI, OTC use was not considered. However, further studies are required to understand the safety and the magnitude of global OTC use of PPIs.

Clinical implications

Based on the findings, this review recommends three key clinical practices for healthcare professionals to mitigate the overuse of PPIs. First, regular reviewing of PPI prescription and documenting indications for continual PPI use. This helps recognize whether the patient still has the initial indication for prescribing, or if the medicine was intended for a short-term use only.

Second, deprescribing (stopping or stepping down or reducing to intermittent use, on-demand use, or lower dose) of PPIs, when there is no appropriate ongoing indication or evidence of benefit [3, 94]. The NICE guidelines recommend a minimum yearly review of PPI prescriptions, and any unindicated drug should be stopped or stepped down if possible [3]. This decreases the treatment cost, unnecessary health harms, and also prevent clinically significant drug interactions including situations where concomitant use of omeprazole will increase the level (e.g., mavacamten) or decrease the effect (e.g., clopidogrel) of medicines by affecting CYP2C19 enzyme metabolism and by increasing gastric pH (e.g., increase the effect of digoxin) [95].

The risk of rebound acid hypersecretion after abrupt withdrawal of long-term therapy [9] discourages patients from stopping the treatment. Dills et al., in their systematic review, found that PPIs are one of the drugs most resistant to deprescribing [96]. Hence, educating and empowering patients about the reasons for deprescribing ae important to ensure the success of the action.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review is the first to describe the global PPI use in the general population of more than 28 million users from 65 studies in 23 different countries. While several studies have reported on the irrational use of PPIs, the increased use of PPIs, and the increased spending on PPIs [18, 26, 37, 48, 60, 62, 97], no other study has evaluated the global utilization of PPIs (including user demographics, magnitude of use, and clinical use patterns) within the general population.

The limitations should be acknowledged. First, we could not investigate the PPI prescribing disparities across income, education level, other comorbidities, and body mass index (BMI). These variables were not routinely reported in the studies analyzed. Second, there was data loss when finding the best fitting age bands, which was necessary due to the inconsistent age groups used within different studies. Attempts were made to align age bands for this analysis such that the least amount of data (total users = 4.2%, new users = 3.2%) was lost while still providing sensible age groupings.

Third, while the national and regional studies with generalizable populations compared in this review provide insight into country specific trends, it is important to acknowledge differences in observation periods. Additionally, it is not possible to determine policy changes, funding, and availability status which may have influenced the prescribing of PPIs.

Conclusion

Global PPI use is significant, with nearly 25% of the adult source population prescribed a PPI. PPI use was reported across the adult life span, with 63% of users being under the age of 65 and 37% being over the age of 65. Females and those of “White” ethnicities had the highest use; however, this may be influenced by the populations studied in the published literature. Most users were on higher doses, and 25% of PPI users continued therapy for longer than one year, with almost a third of patients continuing over three years. Omeprazole was the most frequently prescribed PPI, followed by esomeprazole.

Given the widespread use of this medication and increasing concern regarding long-term use, the review provides a catalyst to support more rational use, particularly with unnecessarily prolonged use.

Data availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Howden CW, Ballard ED, Koch FK, Gautille TC, Bagin RG (2009) Control of 24-hour intragastric acidity with morning dosing of immediate-release and delayed-release proton pump inhibitors in patients with GERD. J Clin Gastroenterol 43(4):323–326

New Zealand Formulary (NZF) (2021) New Zealand Formulary (NZF), NZF v[114]. Available from: www.nzf.org.nz. Accessed 1 Dec 2021

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2019) Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management Clinical guideline (CG184). Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg184/chapter/Appendix-A-Dosage-information-on-proton-pump-inhibitors. Accessed on 1 Dec 2021

Hu X, You X, Sun X, Lv J, Wu Y, Liu Q et al (2018) Off label use of proton pump inhibitors and economic burden in Chinese population: a retrospective analysis using claims database. Value in Health 21:S82–S83

Ntaios G, Chatzinikolaou A, Kaiafa G, Savopoulos C, Hatzitolios A, Karamitsos D (2009) Evaluation of use of proton pump inhibitors in Greece. Eur J Intern Med 20(2):171–173

National Health Service (NHS Digital). Prescription cost analysis -England (2020/2021) 2020. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/378445/prescription-cost-analysis-top-twenty-chemicals-by-items-in-england/ Accessed 27 Sept 2021

ClinCalc.com. Omeprazole. Drug usage statistics, United States 2013-2019. Available from: https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Omeprazole. Accessed 9 Jun 2022

Mishuk AU, Chen L, Gaillard P, Westrick S, Hansen RA, Qian J (2020) National trends in prescription proton pump inhibitor use and expenditure in the United States in 2002–2017. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Guidance for safe and effective use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). 2020. Available from: https://www.barnsleyccg.nhs.uk/CCG/20Downloads/Members/Medicines/20management/Area/20prescribing/20committee/201803-04/20-/20APC/20Memo/20Enclosure/20-/20Guidance/20for/20Safe/20and/20Effective/20use/20of/20Proton/20Pump/20Inhibitors/20-/20March-April/202018.pdf. Accessed on 26 Apr 2022

Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, Welch V (2020) Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1. (updated September 2020). Cochrane. Available from https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v6.1

Page M, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjn71

Braund R, Shanika, LGT, Reynolds, A, Pattison S (2020) Use of proton pump inhibitors to reduce stomach acidity: a systematic review of global trends and practices. Prospero CRD42020167968. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020167968

Reynolds AN, Diep Pham HT, Montez J, Mann J (2020) Dietary fibre intake in childhood or adolescence and subsequent health outcomes: a systematic review of prospective observational studies. Diabetes Obes Metab 22(12):2460–2467

Rohatgi A (2020) WebPlotDigitizer Version 4.2. https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer

WHO (2022) collaborating centre for drug statistics methodology. ATC/ DDD Index

Antoniou TP, Macdonald EMM, Hollands SM, Gomes TM, Mamdani MMPMPH, Garg AXMDP et al (2015) Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ open 3(2):E166–E71

Biyik M, Solak Y, Ucar R, Cifci S, Tekis D, Polat İ et al (2017) Hypomagnesemia among outpatient long-term proton pump inhibitor users. Am J Ther 24(1):e52–e55

Brusselaers N, Engstrand L, Lagergren J (2018) Maintenance proton pump inhibition therapy and risk of oesophageal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol 53:172–177

Cahir C, Fahey T, Tilson L, Teljeur C, Bennett K (2012) Proton pump inhibitors: potential cost reductions by applying prescribing guidelines. BMC Health Serv Res 12(1):1–8

Casula M, Scotti L, Galimberti F, Mozzanica F, Tragni E, Corrao G et al (2018) Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of ischemic events in the general population. Atherosclerosis 277:123–129

Chan A, Liang L, Tung ACH, Kinkade A, Tejani AM (2018) Is there a reason for the proton pump inhibitor? An assessment of prescribing for residential care patients in British Columbia. Canadian journal of hospital pharmacy 71(5):295–301

Chen Y, Liu B, Glass K, Du W, Banks E, Kirk M (2016) Use of proton pump inhibitors and the risk of hospitalization for infectious gastroenteritis. PloS one 11(12):e0168618–e

Chey WD, Mody RR, Wu EQ, Chen L, Kothari S, Persson B et al (2009) Treatment patterns and symptom control in patients with GERD: US community-based survey. Curr Med Res Opin 25(8):1869–1878

Claessens AAMC, Heerdink ER, Van Eijk JTM, Lamers CBHW, Leufkens HGM (2000) Safety review in 10,008 users of lansoprazole in daily practice. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 9(5):383–391

Clooney AG, Bernstein CN, Leslie WD, Vagianos K, Sargent M, Laserna-Mendieta EJ et al (2016) A comparison of the gut microbiome between long-term users and non-users of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 43(9):974–984

Daniels B, Pearson S-A, Buckley NA, Bruno C, Zoega H (2020) Long-term use of proton-pump inhibitors: whole-of-population patterns in Australia 2013–2016. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 13:1756284820913743–

Davies M, Wilton LV, Shakir SAW (2012) Safety profile of esomeprazole: results of a prescription-event monitoring study of 11 595 patients in England. Drug Saf 31(4):313–323

de Vries F, Cooper AL, Cockle SM, van Staa TP, Cooper C (2009) Fracture risk in patients receiving acid-suppressant medication alone and in combination with bisphosphonates. Osteoporos Int 20(12):1989–1998

Ding J, Heller DA, Ahern FM, Brown TV (2014) The relationship between proton pump inhibitor adherence and fracture risk in the elderly. Calcif Tissue Int 94(6):597–607

Doell A, Walus A, To J, Bell A (2018) Quantifying candidacy for deprescribing of proton pump inhibitors among long-term care residents. Can J Hospital Pharm 71(5):302–307

Fattahi MR, Niknam R, Shams M, Anushiravani A, Taghavi SA, Omrani GR et al (2019) The association between prolonged proton pump inhibitors use and bone mineral density. Risk management and healthcare policy 12:349–355

Gadzhanova SV, Roughead EE, Mackson JM (2010) Initiation and duration of proton pump inhibitors in the Australian veteran population. Intern Med J 42(5):e68–e73

Gendre P, Mocquard J, Artarit P, Chaslerie A, Caillet P, Huon JF (2022) (De)Prescribing of proton pump inhibitors: what has changed in recent years? an observational regional study from the French health insurance database. BMC Prim Care 23(1):341

Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, Broich K, Maier W, Fink A et al (2016) Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol 73(4):410–416

Gray SL, Walker RL, Dublin S, Yu O, Aiello Bowles EJ, Anderson ML et al (2018) Proton pump inhibitor use and dementia risk: prospective population-based study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS) 66(2):247–253

Haenisch B, von Holt K, Wiese B, Prokein J, Lange C, Ernst A et al (2014) Risk of dementia in elderly patients with the use of proton pump inhibitors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 265(5):419–428

Hálfdánarson ÓÖ, Pottegård A, Björnsson ES, Lund SH, Ogmundsdottir MH, Steingrímsson E et al (2018) Proton-pump inhibitors among adults: a nationwide drug-utilization study. Therap Adv gGastroenterol 11:1756284818777943–

Hendrix I, Page AT, Korhonen MJ, Bell JS, Tan ECK, Visvanathan R et al (2019) Patterns of high-dose and long-term proton pump inhibitor use: a cross-sectional study in six South Australian residential aged care services. Drugs -- real world outcomes 6(3):105–113

Hermos JA, Young MM, Fonda JR, Gagnon DR, Fiore LD, Lawler EV (2012) Risk of community-acquired pneumonia in veteran patients to whom proton pump inhibitors were dispensed. Clin Infect Dis 54(1):33–42

Hong KS, Kang SJ, Choi JK, Kim JH, Seo H, Lee S et al (2013) Gastrointestinal tuberculosis is not associated with proton pump inhibitors: a retrospective cohort study. World J Gastroenterol: WJG 19(2):258–264

Hughes JD, Tanpurekul W, Keen NC, Ee HC (2009) Reducing the cost of proton pump inhibitors by adopting best practice. Qual Prim Care 17(1):15–21

Jarbøl DE, Lykkegaard J, Hansen JM, Munck A, Haastrup PF (2019) Prescribing of proton-pump inhibitors: auditing the management and reasons for prescribing in Danish general practice. Fam Pract 36(6):758–764

Jena AB, Sun E, Goldman DP (2012) Confounding in the association of proton pump inhibitor use with risk of community-acquired pneumonia. Journal of general internal medicine : JGIM 28(2):223–230

Kim S, Lee H, Park CH, Shim CN, Lee HJ, Park JC et al (2015) Clinical predictors associated with proton pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia. Am J Ther 22(1):14–21

Koggel LM, Lantinga MA, Büchner FL, Drenth JPH, Frankema JS, Heeregrave EJ et al (2022) Predictors for inappropriate proton pump inhibitor use: observational study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 72(725):e899–e906

Kojima Y, Takeuchi T, Sanomura M, Higashino K, Kojima K, Fukumoto K et al (2018) Does the novel potassium-competitive acid blocker vonoprazan cause more hypergastrinemia than conventional proton pump inhibitors? A multicenter prospective cross-sectional study Digestion 97(1):70–75

Larsen MD, Schou M, Kristiansen AS, Hallas J (2014) The influence of hospital drug formulary policies on the prescribing patterns of proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70(7):859–865

Lassalle M, Le Tri T, Bardou M, Biour M, Kirchgesner J, Rouby F et al (2019) Use of proton pump inhibitors in adults in France: a nationwide drug utilization study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 76(3):449–457

Lee J, Mark RG, Celi LA, Danziger J (2016) Proton pump inhibitors are not associated with acute kidney injury in critical illness. J Clin Pharmacol 56(12):1500–1506

Ma J, Gervais A, Lanouette J (2008) Preferential listing of a PPI: compliance with policy in a Canadian military population. Formulary (Cleveland, Ohio) 43(12):436

Machado-Alba J, Fernández A, Castrillón JD, Campo CF, Echeverri LF, Gaviria A et al (2013) Prescribing patterns and economic costs of proton pump inhibitors in Colombia. Colomb Med (Cali) 44(1):13–18

Mafi JN, May F, Kahn KL, Chong M, Corona E, Yang L et al (2019) Low-value proton pump inhibitor prescriptions among older adults at a large academic health system: harmful proton pump inhibitors in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc (JAGS) 67(12):2600–2604

Mares-García E, Palazón-Bru A, Martínez-Martín Á, Folgado-de la Rosa DM, Pereira-Expósito A, Gil-Guillén VF (2017) Non-guideline-recommended prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in the general population. Curr Med Res Opin 33(10):1725–1729

Martin RM, Dunn NR, Freemantle S, Shakir S (2000) The rates of common adverse events reported during treatment with proton pump inhibitors used in general practice in England: cohort studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 50(4):366–372

Martin RM, Lim AG, Kerry SM, Hilton SR (1998) Trends in prescribing H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 12(8):797–805

Moriarty F, Bennett K, Cahir C, Fahey T (2016) Characterizing potentially inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in older people in primary care in Ireland from 1997 to 2012. J Am Geriatr Soc (JAGS) 64(12):e291–e296

Muheim L, Signorell A, Markun S, Chmiel C, Neuner-Jehle S, Blozik E et al (2021) Potentially inappropriate proton-pump inhibitor prescription in the general population: a claims-based retrospective time trend analysis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 14:1756284821998928

Nguyen PV-Q, Tamaz R (2018) Inappropriate prescription of proton pump inhibitors in a community setting. Can J Hosp Pharm 71(4):267–271

Nishtala PS, Soo L (2015) Proton pump inhibitors utilisation in older people in New Zealand from 2005 to 2013: proton pump inhibitor utilisation. Intern Med J 45(6):624–629

Othman F, Card TR, Crooks CJ (2016) Proton pump inhibitor prescribing patterns in the UK: a primary care database study: proton pump inhibitor prescription in the UK. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 25(9):1079–1087

Pasina L, Urru SAM, Mandelli S, Giua C, Minghetti P (2016) Evidence-based and unlicensed indications for proton pump inhibitors and patients’ preferences for discontinuation: a pilot study in a sample of Italian community pharmacies. J Clin Pharm Ther 41(2):220–223

Pottegård A, Broe A, Hallas J, de Muckadell OBS, Lassen AT, Lødrup AB (2016) Use of proton-pump inhibitors among adults: a Danish nationwide drug utilization study. Ther Adv Gastroenterol 9(5):671–678

Poulsen AH, Christensen S, McLaughlin JK, Thomsen RW, SØRensen HT, Olden JH et al (2009) Proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer: a population-based cohort study. Br J Cancer 100(9):1503–1507

Rosenberg V, Tzadok R, Chodick G, Kariv R (2021) Proton pump inhibitors long term use-trends and patterns over 15 years of a large health maintenance organization. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 30(11):1576–1587

Rückert-Eheberg IM, Nolde M, Ahn N, Tauscher M, Gerlach R, Güntner F et al (2022) Who gets prescriptions for proton pump inhibitors and why? A drug-utilization study with claims data in Bavaria, Germany, 2010–2018. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 78(4):657–667

Sánchez-Cuén JA, Irineo-Cabrales AB, Bernal-Magaña G, Peraza-Garay FdJ (2013) Inadequate prescription of chronic consumption of proton pump inhibitors in a hospital in Mexico. Cross-sectional study. Revista española de enfermedades digestivas 105(3):131–137

Sarzynski E, Puttarajappa C, Xie Y, Grover M, Laird-Fick H (2011) Association between proton pump inhibitor use and anemia: a retrospective cohort study. Dig Dis Sci 56(8):2349–2353

Schneider JL, Kolitsopoulos F, Corley DA (2016) Risk of gastric cancer, gastrointestinal cancers and other cancers: a comparison of treatment with pantoprazole and other proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 43(1):73–82

Seo SI, Park CH, You SC, Kim JY, Lee KJ, Kim J et al (2021) Association between proton pump inhibitor use and gastric cancer: a population-based cohort study using two different types of nationwide databases in Korea. Gut 70(11):2066–2075

Shah NH, LePendu P, Bauer-Mehren A, Ghebremariam YT, Iyer SV, Marcus J et al (2015) Proton pump inhibitor usage and the risk of myocardial infarction in the general population. PLoS ONE 10(6):e0124653

Sheikh I, Waghray A, Waghray N, Dong C, Wolfe MM (2014) Consumer use of over-the-counter proton pump inhibitors in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 109(6):789–794

Torres-Bondia F, de Batlle J, Galván L, Buti M, Barbé F, Piñol-Ripoll G (2022) Evolution of the consumption trend of proton pump inhibitors in the Lleida Health Region between 2002 and 2015. BMC Public Health 22(1):818

Van Boxel OS, Hagenaars M, Smout A, Siersema P (2009) Socio-demographic factors influence chronic proton pump inhibitor use by a large population in the Netherlands. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 29(5):571–579

Van Soest EM, Siersema PD, Dieleman JP, Sturkenboom MCJM, Kuipers EJ (2006) Persistence and adherence to proton pump inhibitors in daily clinical practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 24(2):377–385

Wallerstedt SM, Fastbom J, Linke J, Vitols S (2017) Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors and prevalence of disease- and drug-related reasons for gastroprotection—a cross-sectional population-based study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 26(1):9–16

Wang Y-T, Tsai M-C, Wang Y-H, Wei JC-C (2020) Association between proton pump inhibitors and asthma: a population-based cohort study. Front Pharmacol 11:607–

Wei J, Chan AT, Zeng C, Bai X, Lu N, Lei G et al (2020) Association between proton pump inhibitors use and risk of hip fracture: a general population-based cohort study. Bone (New York, NY) 139:115502–

Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, Xian H, Balasubramanian S, Al-Aly Z (2016) Proton pump inhibitors and risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 27(10):3153–3163

Yap MH, Yip G, Edwards A, D’Intini V, Tong E (2019) Appropriateness of proton pump inhibitor use in patients admitted under the general medical unit. J Pharm Pract Res 49(5):447–453

Food and Drug Adminisrtration. FDA drug safety communication: Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea can be associated with stomach acid drugs known as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-clostridium-difficile-associated-diarrhea-can-be-associated-stomach. Accessed 10 May 2023

Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: possible increased risk of fractures of the hip, wrist, and spine with the use of proton pump inhibitors. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm213206.htm. Accessed 10 May 2023

Yamasaki T, Hemond C, Eisa M, Ganocy S, Fass R (2018) The changing epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: are patients getting younger? J Neurogastroenterol Motil 24(4):559–569

Morini S, Zullo A, Oliveti D, Chiriatti A, Marmo R, Chiuri DA et al (2011) A very high rate of inappropriate use of gastroprotection for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy in primary care: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Gastroenterol 45(9):780–784

Rababa M, Rababa’h A (2021) The inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors and its associated factors among community-dwelling older adults. Heliyon 7(7):e07595

Guillot J, Maumus-Robert S, Marceron A, Noize P, Pariente A, Bezin J (2020) The burden of potentially inappropriate medications in chronic polypharmacy. J Clin Med 9(11):3728

Pratt NL, Kalisch Ellett LM, Sluggett JK, Gadzhanova SV, Ramsay EN, Kerr M et al (2016) Use of proton pump inhibitors among older Australians: national quality improvement programmes have led to sustained practice change. Int J Qual Health Care 29(1):75–82

Maes ML, Fixen DR, Linnebur SA (2017) Adverse effects of proton-pump inhibitor use in older adults: a review of the evidence. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 8(9):273–297

Transparency Market Research. Proton pump inhibitors market - Global industry analysis, size, share, growth, trends, and forecast 2016 - 2024. Available from: https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/proton-pump-inhibitors-market.html. Accessed 14 Jan 2020

Mordo Intelligence (2021) Proton pump inhibitors market - Growth, trends, Covid-19 impact, and forecasts (2022 - 2027). Available from: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/proton-pump-inhibitors-market#:~:text=Market%20Overview,forecast%20period%2C%202021-2026. Accessed 31 Jan 2022

El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J (2014) Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut 63(6):871–880

Medsafe - New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority (2010) Proposal for reclassification of Losec® tablets Omeprazole 10 mg to pharmacy medicine. Available from: https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/class/Agendas/agen44-2-Omeprazole-Submission-Publication.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (2018) Public assessment report - Pharmacy to general sales list reclassification Omeprazole 20mg gastro-resistant tablets. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/949109/Omeprazole_20mg_Gastro-Resistant_Tablets_PAR.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Cohn J (2016) The drug price controversy nobody notices. Milbank Q. 94(2):260–263

Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, Boghossian T, Pizzola L, Rashid FJ et al (2017) Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can Fam Physician 63(5):354–364

Medscape. Available from: https://reference.medscape.com/drug/prilosec-omeprazole-341997#3. Accessed 9 June 2022

Dills H, Shah K, Messinger-Rapport B, Bradford K, Syed Q (2018) Deprescribing medications for chronic diseases management in primary care settings: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Dir Assoc 19(11):923-935.e2

Hollingworth S, Duncan EL, Martin JH (2010) Marked increase in proton pump inhibitors use in Australia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 19(10):1019–1024

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: LGT Shanika, AN Reynolds, S Pattison, and R Braund. Developing the search terms and conducting the searches: AN Reynolds. Data curation: LGT Shanika and R Braund. Methodology: LGT Shanika, AN Reynolds, S Pattison, and R Braund. Formal analysis: LGT Shanika. Writing—original draft: LGT Shanika. Writing—review and editing: LGT Shanika, AN Reynolds, S Pattison, and R Braund.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Prior presentations: New Zealand Society for Oncology Conference 2021; 27th – 29th January 2022

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shanika, L.G.T., Reynolds, A., Pattison, S. et al. Proton pump inhibitor use: systematic review of global trends and practices. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 79, 1159–1172 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-023-03534-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-023-03534-z